- Book Cricket

- Color-Color-What-Color

- Hide-and-Seek

- Musical chairs

- Name-Place-Animal-Thing

- Pitthu

- Poshan-Pa-Bhai-Poshan-Pa

- Raja-Rani-Mantri-Chor

- Tic-Tac-Toe

- London Statue

- Lock-and-Key

- Antakshari

Before the Stick Cricket smartphone app, before fantasy cricket leagues, heck, even before Brian Lara Cricket, there was a virtual cricket simulation that took our fancies by storm. That made us forget that unit tests were right around the corner. That made even the drabbest English 2 class rattle with fever pitch excitement. Held in the famous stadium ‘IV D’, this was cricket by the book. Literally. There was no margin for error, no third umpires and no room for match fixing (unless you intentionally dog eared pages 56, 106 and 246 hoping your opponent won’t catch on to your blatant deception). Cover drives were replaced by brown covers, commentaries were replaced by past participles and ducks, by “Duck! The teacher’s coming!” Scores were tallied and victors were declared. The best part? You were having fun with math and you didn’t even know it.

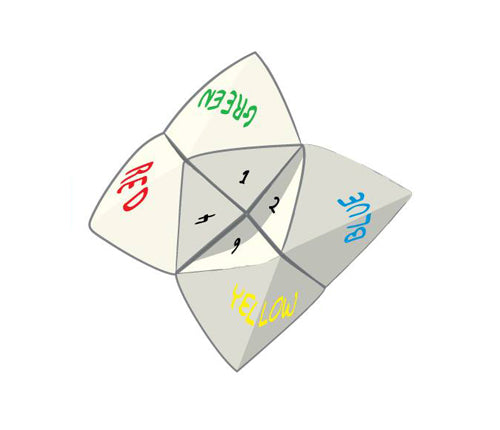

Before “Which Game of Thrones realm do you belong in?” or “Which F.R.I.E.N.D.S character would be your soulmate?” or some such online personality test, we had a paper version that started it all. First you chose one of the four colors. Sometimes, when you didn’t have crayons (which usually meant that you didn’t have drawing class that day) the colors were just written down. Then you chose a one of the two numbers written under a colour fold. What followed was the moment of truth. Depending on what the topic of the day was, you would find out who you would end up marrying, what your future job was going to be and which superhero you secretly were. All before the recess bell rang.

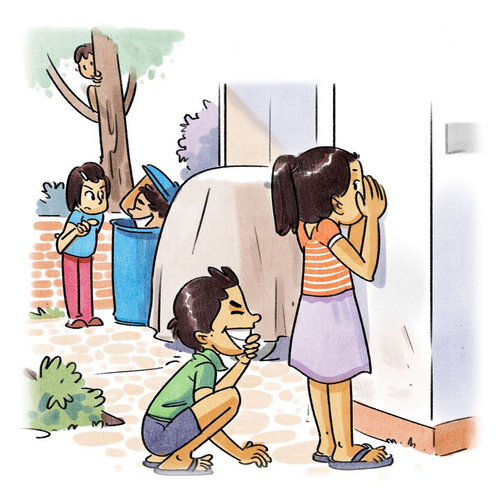

This was an after 7 game; a game that combined the thrill of pursuit with the uncertain camouflage of darkness. No sporting equipment required, this was a hands free game. Your brush with what you thought espionage entailed. Terraces were out of bounds and meant immediate disqualification. No hiding in the water pump room. Those were the rules. But rules were meant to be broken. Especially when mother called out from the balcony saying food was ready.

No society function or extended family gathering was complete without the inclusion of musical chairs as a part of the evening’s entertainment. All you needed were a few (alternately front and back facing) chairs, a music player and willing participants (always one more than the number of chairs) to play this physical version of passing the parcel. Quite literally a game of thrones, musical chairs taught us a valuable lesson about life. That old people really like sitting. You realize that midway across a round when a beloved aunt pushes you away hastily in her quest for a Nilkamal chair. As fun as it was, musical chairs are the reason why you still shy away from politics.

“Start!”Four seconds pass.“Stop!”“What letter?”“M.”“Impossible! How did you count the alphabets so fast?”“I’m a smarty okay? And you can’t count alphabets. They’re not numbers IDIOT!”“M’aaaaaaaaaaaaam! <insert name here> called me IDIOT.”*The whole class spontaneously bursts into laughter*Alphabets were the trajectory, proper and common nouns were the ammunitions and us, the royal admirals of our free periods. No words were too sacred. No rules too grounded. Ah, the spoils of war.

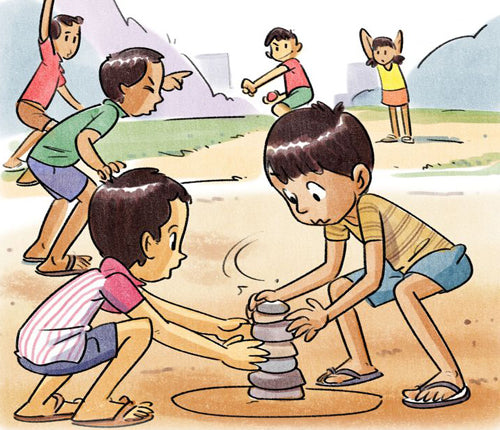

Seven stackable stones (usually pieces of broken tiles), one ball (the same one we just played cricket with) and two teams with nothing to lose (except the ball, it was a new ball – it still had the sticker on). Pitthu (or Lagori in Western India) coupled elements of kabaddi, dodgeball and architecture. Clearly based on the cosmic cycles of creation and destruction (not really, though), one team’s job was to stack stones while the other team tried to break that stack. If the defending team reassembles the stack before all its members are hit by the weaponized ball, it wins. If not, they can always exact sweet revenge by being the attacking team, the next game.

The postman may ring twice but this game made the postman steal those rings. Before you knew about postal fraud, you knew about the postman who conned people out of their belongings.The whole verse went:

‘Poshan pa Bhai Poshan pa,Daakiye Ne Kya Kiya?Sau Rupaye Ki Ghadi Churayee,Aath Aane Ki Rabri Khayee,Ab To Jail Mein Jaana Padega,Jail Ki Roti Khanee Padegi,Jail Ka Pani Peena Padega,Ab To Jail Mein Jaana Padega.’

And to this inflation free tune, two ‘gatekeepers’ would stand on either side with their hands inclined and outstretched to form an arch. (So in effect, the gate keepers were sentient gates) As soon as the song ended, the ‘gates’ would suddenly close around you, trapping you. Possibly as a metaphor for life insurance. Who knows.

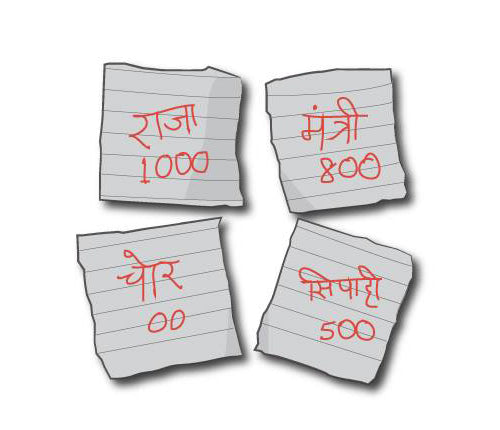

A game that seamlessly blended monarchy and identity theft. A classic royal whodunit. The participants (four or more) would pick up chits that hold their secret identity. Each secret identity would be allotted certain points. The game required the ‘Sipahi’ (also sometimes called Senapati or Police) to declare himself. His job was to guess who the ‘chor’ (the thief) was. Guess the wrong person and risk royal treason (oh, and your points go to the real thief). Guess it right and be rewarded. Sometimes the game was customized to add characters like ‘Hawaldar’ and ‘Vidushak’. It doesn’t matter when we played poker, this is the game where we learnt our poker faces.

The good old X and 0s. Carrying the banners knots and crosses, a war was waged on a 3 by 3 grid. We fought tooth and nail for diagonal, vertical and horizontal supremacy. And when it was over, we played again. Best 2 out of 3, best 3 out of 5 and so on. But then the teacher would walk in and cut our competition short. Begrudgingly, we’d grant each other a ‘to be continued...’ status. It wasn’t over. It was never over.

Whether it was Horatio Nelson at the Trafalgar Square or that of Sherlock Holmes at 22B BakerStreet, we didn’t know. Although some claimed it was the Big Ben. Which begged the existential question of that decade: Are clock towers statues? But dubious nomenclature aside, London statue had the catcher at a very distinct advantage. He or she would have the power to control time by saying ‘statue’ and incapacitating the runners mid-sprint. The runners’ goal would be to breach the catcher’s territory as the catcher (quite villainously so) tries to make the ‘statues’ move through \verbal cues so as to get them out of the game. Hollywood has nothing on the psychological thrillers we made up as kids.

Sometimes called ‘Vish-Amrit’, Lock and Key acted out like a Greek myth. The catcher touches you, you freeze instantly. But the other runners who haven’t been caught yet can ‘unfreeze’ you from this sorcery. But unfreezing you would mean increasing their chances of being caught as the catcher would generally lurk around his prize catch. Only the bravest of them would take up this rescue mission. Some sacrificed their mobility so you could be free. Now you owe them your life but another ‘lock’ would mean watching the rest of the game as a viewer and not as a participant. This was also the time you found out which direction your moral compass pointed towards.

Where did it end? Where did it begin? Was it the syllable or was it the sound? It was a race against time. Failing which the doomsday clock of ‘Tick-Tick-One, Tick-tick-Two...’ would begin chiming. The game was entirely about playful deadlines and shattered remnants of what was once a generation gap. Fathers, Uncles, Cousins – It didn’t matter. They were all pitted against each other and they all had an equal chance of winning. That is, of course, until an unexpected family member (usually a strict grandparent) breaks into an old Rafi classic. Antakshari made spellings fun and lyrics, weapons. The ultimate picnic game that kept making guest appearances in weddings, festivals and school trips – You didn’t need a reason to play Antakshari, you just needed a moment.